The Best Plumber in Brooklyn

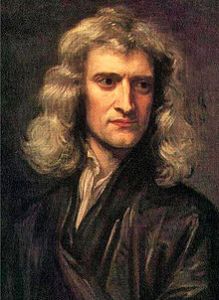

Sir Isaac Newton, 1643-?

New Yorkers are well-accustomed to seeing celebrities and we have our own unique way of dealing with them: we ignore them. As a rule, our disdain of luminaries is applied only to the living, which only makes sense. So, we don’t expect to see dead celebrities. But the same facelessness that can hide one from the public eye can also hide one from history. That’s what I discovered one evening when I met the best plumber in Brooklyn.

Not long ago, I was sitting on a park bench on the Promenade in Brooklyn Heights enjoying the view of the sun setting over the Manhattan skyline. As I scanned the landscape, I noticed a middle-age man sitting on the next bench who looked strangely familiar. There was something about his aquiline nose and high forehead that made me almost certain I’d seen him before.

And, then it struck me.

“Excuse me,” I ventured. “I’m sure you hear this all the time, but you look almost exactly like the portraits I’ve seen of Isaac Newton. It’s really uncanny!”

“Yes, I do hear that quite often,” he replied. “I’ve become accustomed to it over the years and I no longer take offense.”

I detected a distinct upper-class British accent. This made me all the more curious and I had to push the conversation further.

“You’re accent,” I said.” “You must be from the U.K. No wonder people mention the resemblance. Where are you from?”

“Lincolnshire, in the East Midlands. Maggie Thatcher’s home turf.”

“Wasn’t Isaac Newton born in that region, too?”

“Yes, but I try not to draw attention to that fact. Let me guess. You were a science or mathematics student, weren’t you?”

“Yes. My undergraduate degree was in physics. How did you know?”

“Who else would recognize me?”

“You mean Newton, don’t you?”

“That’s what I said.”

“What? Wait a minute! Are you trying to tell me that you really are Isaac Newton?”

“I’m not trying to do anything, my good man. I stated it plainly. You need to pay closer attention.”

“You’ve got to be kidding! This is Brooklyn. It’s the 21st century.”

“I see you’re another keenly observant American.”

“Newton died in 1727. That’s more than 280 years ago.

“Don’t believe everything you read. I never have.”

“Newton was born in 1643. That would make you…372 years old. That’s impossible!”

“You know dates and sums. Good for you. Actually it was December 25th, 1642. We used the Julian calendar back then.”

“How confusing for you now,” I ventured cautiously, attempting to reach a sort of sarcasm parity with my over-articulate new acquaintance.

“I’ve had plenty of time to accustom myself to your silly little Gregorian calendar,” he replied coldly. “Dates and time are of little consequence to me. I live in the now. It is always now. It will always be now. The past is gone and less than a memory. And, unless you have it on good authority that the world will end shortly, I care nothing for the future, either. This day is ending and tomorrow will bring me no surprises and precious few challenges.”

“You’re either clinically depressed, bored senseless, delusional, biologically immortal, or some combination of all of the above,” I thought, not intending to do so out loud. “I’ll put my money on depressed and delusional.”

“You Americans will put your money on damn near anything without any regard for risk or odds. So, you’ll forgive me if I feel less than flattered.”

But, don’t you find it even slightly preposterous to claim to be more than three-and-a-half centuries old?” I inquired rhetorically.

“I never claimed anything, you cretin!” he snapped, glaring at me with eyes of such an intense blue that they appeared to be illuminated from within. I suddenly remembered that Isaac Newton was said to have intensely blue eyes and a dangerously bad temper.

Time to leave, I thought.

“No one pays attention to anything anymore!” he lamented, his voice suddenly betraying a profound loneliness. “I admitted only to having been around a long time. You’ve heard of the Philosophers’ Stone, I suppose? I refuse to call it the ‘sorcerers’ stone.’ Makes it sound tawdry.”

“You mean the thing alchemists thought would turn base metals into gold?”

“Yes, that one. It has other properties, though. I mean, really; how much gold can one person use, anyway?”

“I could use some.”

“You? You’d probably trade it all for lottery tickets, or some other such foolishness,”

“There’s nothing wrong with wanting a bit more money!” I said, defensively.

“Really? How about a bit more life? How about a vastly extended lifespan?”

“Can I get more life in my years or does this deal only include more years in my life?”

“If that’s an attempt at sarcasm, it’s rather disappointing, especially for an American who knows Isaac Newton’s birthday.”

“Well, if you’re trying to convince me that you’ve found a cure for aging and you’re 372 years old, sarcasm is all you’re going to get.”

“Luddite! Small-minded skeptic! Moron!”

“I thought Luddites just hated machines.”

“Yes, you’re really more of a pedant.”

“Thanks. I feel much better. Vindicated, really.”

“I’ll ignore that.”

“Well, I can’t ignore the math and fact that you don’t look a day over forty. Just how were you able to live so long,” I ventured, deliberately avoiding the word ‘immortality.’

“Yes I avoid mentioning immortality, too. It’s unnecessarily provocative and I’m not sure it’s in any way accurate.”

Crazy or not, this guy was entertaining. So I suppressed my incredulity and just let him talk.

“It’s all alchemy, you know,” he continued. “You all call it chemistry now, biochemistry, inorganic chemistry, metallurgy, all sorts of minutely defined studies. It was so much simpler when all we had to contend with was philosophy, mathematics, and alchemy.”

“What about astronomy?” I asked, having temporarily forgotten I was talking to a lunatic.

“Oh, that too. But alchemy was the ticket. Do enough of it long enough and you’re bound to stumble across something useful.”

Now he seemed to be genuinely reminiscing. It was clear that he believed what he was saying, even if I wasn’t convinced.

“So it was an accident?”

“Yes,” he sighed. “I was messing around with different fruits and herbs, some from the New World—Brazil, if you must know—and some from the Far East. All I wanted was a remedy for indigestion and flatulence. My God, I had the worst wind!”

“So let me get this straight,” I said cautiously. “You were looking for Pepto-Bismol or Alka-Seltzer and you just happened upon immortality?” My incredulity was back.

“Funny, right? That was one of the few times I wasn’t looking for the Philosopher’s Stone!”

“Imagine what you might have found by accident if you looked for a syphilis cure!” I exclaimed.

“I did and it was a bloody mess, literally.”

“What?”

“Don’t ask. It’s a painful memory.”

“Okay.” I figured it was time to change the subject and bring us back to the present. “So, you wound up here. You haven’t been outed yet, so I guess you’re not doing science anymore. How do you live? What do you do?”

“Oh, I’m a plumber, and a damn good one at that. In fact, I’m the best plumber in Brooklyn!”

“A plumber? You? One of the greatest scientific minds ever?”

“How dare you disparage my chosen profession,” he snapped, his nostrils flaring with anger. “It’s a noble and very profitable profession. I got the idea from Leonard Suskind.”

“The Nobel-winning physicist at Stanford?”

“None other. His father was a plumber and so was he before he took up physics and started dabbling in that Quantum nonsense.”

“I figured you wouldn’t be a fan of Quantum Mechanics. Okay, so you’ve been around for nearly four centuries and you’re a plumber now. But, why choose Brooklyn?” I asked.

“Why? For the same reason I suppose everyone comes to Brooklyn from abroad: for bagels and cheesecake! You bloody well can’t find those in Cambridge, can you? Oh, yes, your beer and falafel aren’t bad, either. Now I really must go. I have an early appointment at a building full of clogged toilets in Park Slope. Here’s my card, if you ever need a plumber—or a physicist.”

The card read “Fallen Apple Plumbing and Heating, I. Newton, Proprietor.” On the back was the phrase, “Enforcing the Law of Gravity since 1993.”

“That was my year of my 350th birthday.”

“Of course it was. Will I see you again, here on the Promenade?”

“Perhaps. Come back in a hundred years and find out.”

“I can’t do that!” I laughed.

He leaned in close and whispered, “Then you’re not taking enough Alka-Seltzer.”

I stopped laughing.

With that he hurried away into the night, momentarily illuminated by a streetlight.

Since then, I’ve been taking Alka-Seltzer three times a day. Who knows? Maybe we’ll both still be here in a century.